CABA

El Foro, de arriba a abajo

«¿Cuál es el punto en Porto Alegre? Un diálogo entre activistas de dos generaciones». Así presentó el sitie www.opendemocracy.org esta conversación entre Susan George -fundadora de Attac y autora del Informe Lugano- con el activista argentino Ezequiel Adamovsky. Esta es la versión en inglés. Prometemos traducción en breve. (como siempre, se aceptan voluntarios).

What is the point of Porto Alegre? Activists from two generations in dialogue

The World Social Forum in Brazil’s Porto Alegre brings together campaigners from around the world in debate over alternatives to globalisation. Here, two key activists – one Argentinian, one Franco-American – discuss frankly the best way forward for a movement at a pivotal moment in its history.

openDemocracy: The agenda of the World Social Forum (WSF) in Porto Alegre this year is huge. What do you see as the priorities for the WSF, and why?

Susan George: The first Forum, in 2000, was about analysing the world situation, and I think as a movement we now largely share a common analysis. The second Forum last year was supposed to be more about making concrete proposals. As I understand it, this year is supposed to be about strategies and how we reach our goals. I hope that will be the overriding concern, although of course such clear-cut distinctions aren’t always possible; there will be new elements of analysis and new proposals. I think a huge agenda can be a good thing if it converges on strategies for change in many different areas, and if it shows that those strategies are similar whatever the goal may be of that huge agenda.

What do I feel are the priorities and why? As I have just written for the Porto Alegre paper, I think that everyone should go with one priority. Mine will be the General Agreement on Trade and Services (GATS) and the World Trade Organisation (WTO) more generally. Porto Alegre is full of such interesting people and so many interesting events that you want to be in twenty-five places at once. If you don’t decide before you get there what you want to do and who you want to do it with, you are going to be frustrated and come back feeling you didn’t really get that much accomplished.

So that’s my advice. I can say what my priorities are, I don’t want to dictate to other people what theirs should be, but I think we should all be concentrating on strategies in whatever area we feel is most important and that we know most about.

Ezequiel Adamovsky: I also think this Forum will deal mainly with strategies, and in that regard I think that one of the most important issues now is how to strengthen the network of movements that has been built up in the last few years. That will be my priority at the WSF.

But I have some concerns. The first is that the Forum risks reproducing, in the way it functions, some features of the society we want to change. There is a danger, for example, that the Forum will become unduly focused around big names or intellectuals who get most of the funding, whilst many grassroots activists can’t afford to attend and don’t get the space they deserve. I certainly don’t mean any offence to Susan personally – it is a general point about the way the Forum seems to work.

I was discussing this a few days ago with friends at the Anti-Eviction Campaign in South Africa. They are really angry about this. A major issue at the Forum will be how to build a global network for the movement. But they can’t afford to be there. Likewise, I think intellectuals should try to meet activists on an equal basis to listen to each other.

There’s a danger that the Forum will become ritualised into an annual meeting with famous intellectuals and big names on panels but without enough real exchange between activists and movements from all over the world.

Susan George: I’m not looking to be a star and I think that many people in the movement that you call the intellectuals aren’t looking to be stars either. It’s simply in my case that I have been working on similar issues for twenty-five years. I said to the WSF organisers when they invited me that the movement was really launched now and that the presence of this or that big name was really not important. I stressed exactly what Ezequiel is saying because the organisers have very little money this year because they have lost some financial support of the local government. I said that they should use whatever little they had to bring people of the kind that Ezequiel is describing.

As far as I know, almost all the northern organisations are paying their own way. Maybe they should be cutting back on some delegations in order to pay for people from organisations like the one Ezequiel mentions in South Africa to go instead. But I don’t think it’s the case that there is a single pot of money out of which some big names are being brought and then other activists aren’t.

But I certainly agree that unless we have contacts with people, as you say, on the ground, grassroots activists, and the others, who are attempting to write about and popularise this movement and to help to channel it into particular directions, I think we have the same goal. Ideally the WSF could be a place where that happens, but you seem to be saying that you don’t think it’s going to happen. I would say that it’s one of the rare places that those things can happen internationally.

Alienating radical voices and movements?

Ezequiel Adamovsky: I have noticed that many radical movements are feeling more and more uncomfortable with the WSF. There have been attempts to create alternative spaces within the Forum, and even outside it. There are some proposals to organise a sort of counter-forum. I see a danger there, and I think that at some point the Forum will have to address the fact that different groups have different approaches to social change.

To put it in simplistic terms, on the one hand, there’s the approach of most non-governmental organisations (NGOs) which want to reinforce the role of civil society as a check on the power of corporations. These NGOs want somehow to restore the balance that society has lost, and make capitalism more humane. Then, on the other hand, there is a more radical approach, shared by some of the social movements and radical collectives, which wants to strengthen the antagonistic movement against capitalism, to fight this society and build a new one.

I don’t believe that there’s any need to put a fence between these two approaches; quite the opposite, I think that we can stay together and it is productive that we meet. But I think that the WSF should provide a space in which radical movements can feel comfortable. I think that radical movements should play a larger role at the Forum than NGOs. For example, the mayor of Buenos Aires, Aníbal Ibarra, usually goes to the Forum. He’s the guy who we’re actually fighting against in the city [see, for example, information about the fight by Buenos Aires subway workers to improve working conditions – oD], so it feels really annoying that we have to share that space with him.

One of the radical groups, Peoples’ Global Action, was in two minds about whether to organise events at the Forum. They have now decided to go, but only after a lot of discussion about whether to hold their events inside or outside the Forum. Likewise, I know that the guys from Indymedia are angry at the Forum because all space for the media has been occupied by corporate media, and there is no space for the alternative or the independent.

Susan George: First, on that single point of the mayor, I’m very interested to hear Ezequiel explaining that people are feeling more and more uncomfortable. I know last year before the French elections we were also irritated that every French politician on the left who was going to run for the presidency was rushing to Porto Alegre to show off. We felt exactly the same way in France as Ezequiel and his movement feel in Buenos Aires.

Secondly, I think it’s always healthy to have people on your left, especially as you get older. Where I would stop that acceptance of having people on your left is if those groups advocate violence. We really have to keep this a peaceful pressure movement, and that pressure should come from many different quarters. Advocating violent action is utterly counterproductive.

But sometimes I simply don’t understa

nd when I hear some people talking about revolution. What do they mean? Taking state power? Well, Lula took state power and he’s hemmed in on every side by the international system. Would it be what the philosopher Paul Virilio in France called the ‘global accident’, where all the banks, all the markets, everything collapses at once? You would have huge chaos and total human misery. I think it would end in fascism.

Nevertheless, I’m absolutely prepared to listen to what Ezequiel calls radical strategies and whatever they can do to help to build a different sort of society. If it’s done in a non-violent way I think we would agree that what this movement has got to do is to create spaces where that kind of new society can be built.

I don’t think it’s quite accurate also to say that all NGOs simply want to make capitalism with a human face. I think people recognise more and more whether they are in the North or the South, and I don’t know whether you qualify my own organisation ATTAC as an NGO, but we certainly don’t think it’s enough to have capitalism which is just slightly nicer. We go a lot further than that.

Ezequiel Adamovsky: People have many different ideas of what a revolution means. The same is true with violence. What is violence to some people is not violence for other people. But what I want to stress is that I don’t think it’s enough for this movement to be what Susan calls a pressure movement. I would like this movement to help us take control of our own lives, not just to pressure the representatives to change the world in ways that we want, or to pressure the state or the corporations to change anything. We need more than that. Maybe that’s one of the issues of strategy that we need to discuss in this forum and in the future.

Avoiding the Comintern syndrome

Ezequiel Adamovsky: I have a third concern about the WSF. There’s a proposal to create a network of networks and movements. It’s a valuable idea but there are dangers. My fear is that it could become centralised, with a homogeneous voice or a visible location. This would actually lead to the destruction of existing networks, which are being built every day and getting stronger every day. To have a sort of secretariat of a network means actually the opposite of a network.

This could lead to struggles for power, which could end up destroying the existing networks. I think that the Forum should rather offer economic and technical support and resources for the network to actually happen rather than try to centralise or give the network a voice or a space, a location. For example, there is this network People’s Global Action, which is being set up at present. It came from an idea of the social movements, and they don’t have many resources at all. They don’t have offices or computers or telephones or anything like that.

So maybe a good idea would be to try to help the existing network to function rather than trying to bring some new central structure into being. I noticed that the idea of this project in the WSF is also being carried out by some of the movements and also by some of the big names.

Susan George:

Ezequiel Adamovsky: I was told that some of the people who are working on this are some of the intellectuals who usually attend the Forum, which is fine, absolutely fine. My concern is that I think this issue should be carried out by the movements themselves – and for that to happen, movements should have the chance to attend the meetings where this issue is being discussed as well as the WSF.

Susan George: I’m completely against the idea of some sort of Comintern which would centralise and try to speak for the entire movement. I think that would be a disaster. So we agree completely about that. When you speak about domesticating the existing network, I haven’t seen a move towards that on the part of groups from the North, but I know that there has been a proposal mostly coming from the Brazilians – principally the CUT and the MST – for some sort of secretariat. Many groups in the North would have more of a tendency to accept a proposal coming from those respected organisations in the South than if it came from others.

So I’m against anything that tries to centralise and I completely agree with you that it would destroy through power struggles what we’ve already built. But when you talk about giving economic and technical resources to movements which are struggling to exist, I wonder where those are going to come from.

Some people think that there’s a lot of money floating around in northern NGOs in particular. Well, there may be in some. But on the whole everything works on volunteer labour, and I think if we want to get economic and technical support for our allies, then the best way to do that is to keep working on issues such as international taxation, reducing the burden of debt, and municipal budgeting systems on the lines of Porto Alegre.

This is where the real money is. Anything else is going to be peanuts. I know People’s Global Action, I worked with them at the very beginning when they hadn’t even called themselves that yet, and I know that they can do a lot with very little. Most movements operate in that way. So let’s be more specific about how we can try to help the existing networks, how they can be identified, how the serious ones can be separated from the less serious ones and then see what we can do together to get those resources.

Organising for a different future

Susan George: I understand your concerns about centralising, but do you object to the sort of declaration that came out of Porto Alegre last year? This was the result of many movements working together. Focus on the Global South and ATTAC played quite a large role. Do you object even to that as a sort of sign of centralisation or a desire to corrupt the thought and the practice of the movement?

Ezequiel Adamovsky: No, I don’t object to any attempt of the movement to come together and to think, produce statements or design a political strategy. But a secretariat or any other form of centralisation would destroy the possibilities of a network.

My priority is to help build networks with other movements. I found that in the past the contacts we have made with groups such as the Anti-Eviction Campaign in South Africa were really productive for us in many ways. We could exchange ideas on many issues from horizontal organising to direct action with them. So the priority should be to keep on learning from other movements and sharing our own experiences with other movements.

Susan George: I understand the means perfectly, but in view of doing what?

Ezequiel Adamovsky: I can only speak about what I would like to do in my own struggles in my own place. I’m an anti-capitalist. I would like to create a completely new society, quite different from the actual one. For that I think that we need to link our struggles with the struggles of others all over the world. That’s why I say that my priority is to build relations with other groups – not only to learn and exchange experiences on a theoretical level, but also to try to organise a common strategy to change the world.

What I have in mind is what we’re actually doing in my own Asamblea every day. We are creating spaces where people can make their own decisions and can live the way they want to live. You get the same idea in many different countries and places: movements which are organised in horizontal ways, as we are, or whatever other means they are using. I think that we are all working towards the same goal, even if we don’t have the same strategy and disagree on certain issues. I think that we have that in common: the idea to create a world where you can decide by yourself.

Susan George: I share that goal. I see the world as it is now as one that is more and more dominated by a tiny minority of transnational forces, who have no intention of allowing people to make their own decisions and live as th

ey want to live, if I may quote Ezequiel.

I think there is an all-out battle against any form of democracy. I see this epitomised at the moment in the WTO, and particularly in the fight against public services against the environment and many other aspects, health, education, etc., as embodied in the GATS. So my goal is to prevent the bastards from going any further than they’ve already gone.

It’s all very well to say we’re going to create spaces where people can make their own decisions. Those decisions are more and more hemmed in by the fact that there isn’t any decent bus service, there is no decent school for your children, food prices are going up because it’s all imported, and housing is impossible inside the city because there’s no social housing, and so on. That’s why I focus on trying to challenge the bastards and get rid of them. And since I can’t do everything I’ve picked one particular corner of that now. My big fight used to be about international debt and I’ve said everything I have to say on that even though I’m still marginally part of that debate.

We must get rid of the killers who have got most of the money, most of the power, and are already in position, controlling most of the structures. For me that’s the urgent task, because without that, what Ezequiel is proposing is simply never going to work.

Ezequiel Adamovsky: I agree with what Susan just said. When I speak of creating spaces where we can live the way we want to live, I mean this in an antagonistic way. I mean that we have to challenge and to confront the power of corporations. But I think we need to do both things at the same time because it’s part of the same issue and the same struggle. You challenge and confront corporations while you are creating something different, a different space which is organised with different rules, different bases.

This is what we’re trying to do with the Asambleas in my neighbourhood of Buenos Aires. We create our own space, which is organised on horizontal principles, but at the same time we need to confront all the time the power of corporations and the state in many ways. For example, we decided to occupy an empty building which belonged to a financial corporation, and we are now in a trial. They are trying to kick us out, so we have to fight that corporation while we are trying to set up a new space, a different space in our neighbourhood. Building a world beyond capitalism always means confronting capitalism. Even if you try to ‘escape’ from them, they simply come for you. They cannot afford to let us escape and build autonomous spaces, because they live on our work, our energy.

Derechos Humanos

A 40 años de la sentencia: ¿Qué significa hoy el Juicio a las Juntas?

Este martes 9 de diciembre se cumplen 40 años de la lectura de la sentencia del Juicio a las Juntas Militares. Habrá un acto en la Corte Suprema de homenaje a los jueces Carlos Arslanián, Ricardo Gil Lavedra, Guillermo Ledesma y Jorge Valerga Aráoz (fallecieron los otros dos integrantes de aquella Cámara Federal: Andrés D’Alessio y Jorge Torlasco).

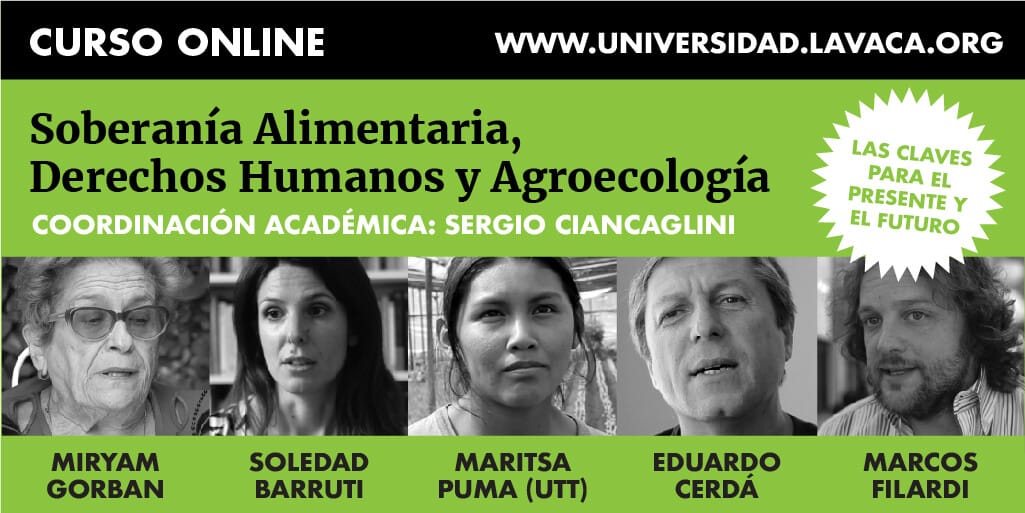

Testigo privilegiado de muchas de las audiencias por su cobertura para el diario La Razón, Sergio Ciancaglini, actual periodista de MU y coautor del libro Nada más que la verdad (junto a Martín Granovsky) repasa escenas, revelaciones y el contexto de una experiencia inédita en el mundo en la que por primera vez se juzgó un crimen masivo cometido desde el Estado por una dictadura.

Los testigos, los alegatos, las sorpresas, la ubicación de la locura y de la cordura. Los gestos de Videla, Massera y Viola. Los testimonios de las mujeres sobre los ataques y violaciones que sufrieron. El antisemitismo militar. El peso desde el cual los médicos calculaban que era factible torturar. El sitio de lo impensable, y la proyección de aquella historia pensando en los derechos humanos del presente.

Por Sergio Ciancaglini

Actualidad

Sin pan y a puro circo: la represión a jubilados para tapar otra derrota en el Congreso

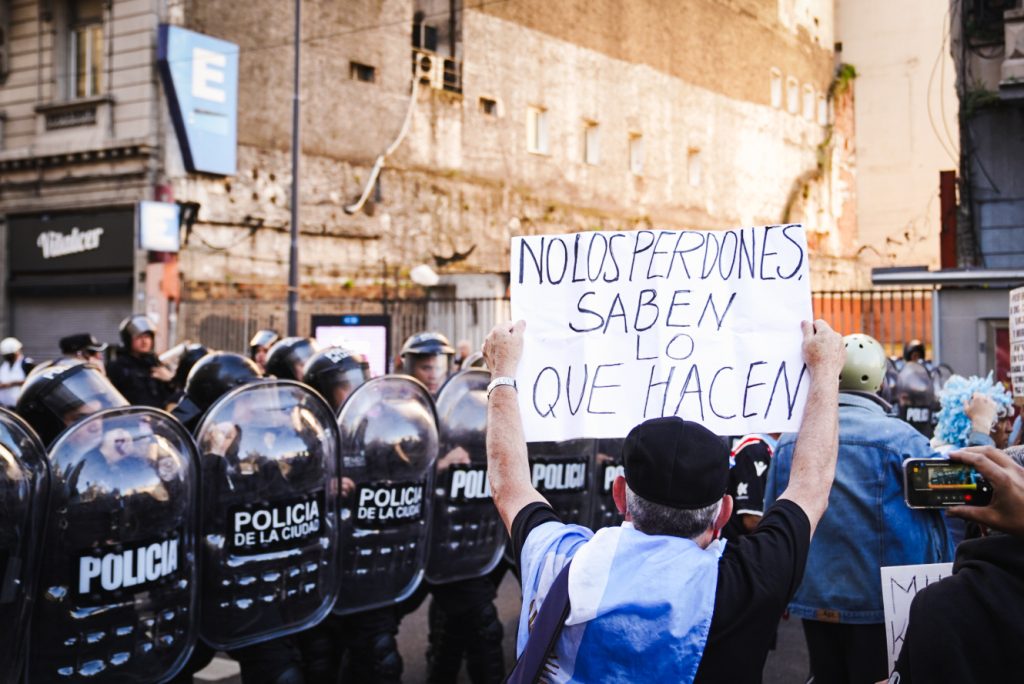

La marcha pacífica de jubilados y jubiladas volvió a ser reprimida por la Policía de la Ciudad para impedir que llegara hasta la avenida Corrientes. La Comisión Provincial por la Memoria confirmó cuatro detenciones (entre ellas, un jubilado) que la justicia convalidó y cuatro personas heridas. Una fue una jubilada a quien los propios manifestantes […]

La marcha pacífica de jubilados y jubiladas volvió a ser reprimida por la Policía de la Ciudad para impedir que llegara hasta la avenida Corrientes. La Comisión Provincial por la Memoria confirmó cuatro detenciones (entre ellas, un jubilado) que la justicia convalidó y cuatro personas heridas. Una fue una jubilada a quien los propios manifestantes salvaron de que los uniformados la pasaran por arriba. En medio del narcogate de Espert, quien pidió licencia en Diputados por “motivos personales”, las imágenes volvieron a exhibir la debilidad del Gobierno, golpeando a personas con la mínima que no llegan a fin de mes, mientras sufría otra derrota en la Cámara baja, que aprobó con 140 votos afirmativos la ley que limita el uso de los DNU por parte de Milei.

Por Francisco Pandolfi y Lucas Pedulla.

Fotos: Juan Valeiro.

Un jubilado de setenta y tantos eleva un cartel bien alto con sus dos manos.

“Pan y circo”, dice.

Pero el “pan” y la “y” están tachados, porque en este miércoles, como en esta época, lo que falta de pan sobra de circo. El triste espectáculo lo ofrece una vez más la policía, hoy particularmente la de la Ciudad, que desplegó un cordón sobre Callao, casi a la altura de Sarmiento, para evitar que la pacífica movilización de jubilados y jubiladas llegara hasta la avenida Corrientes. Detrás de los escudos, aparecieron los runrunes de la motorizada para atemorizar. Y envalentonados, los escudos avanzaron contra todo lo que se moviera, con una estrategia perversa: cada tanto, los policías abrían el cordón y de atrás salían otros uniformados que, al estilo piraña, cazaban a la persona que tenían enfrente. Algunos zafaron a último milímetro.

Pero los oficiales detuvieron a cuatro: el jubilado Víctor Amarilla, el fotógrafo Fabricio Fisher, un joven llamado Cristian Zacarías Valderrama Godoy, y otro hombre llamado Osvaldo Mancilla.

Las detenciones de Cristian Zacarías y del fotógrafo Fabricio Fisher. La policía detuvo al periodista mientras estaba de espaldas. Foto: Juan Valeiro para lavaca.org

En esa avanzada, una jubilada llamada María Rosa Ojeda cayó al suelo por los golpes y fue la rápida intervención de los manifestantes, del Cuerpo de Evacuación y Primeros Auxilios (CEPA), y de otros rescatistas los que la ayudaron. “Gracias a todos ellos la policía no me pasó por encima”, dijo. Su única arma era un bastón con la bandera de argentina.

Como en otros miércoles de represión, la estrategia pareciera buscar que estas imágenes opaquen aquellas otras que evidencian el momento de debilidad que atraviesa el Gobierno. Hoy no sólo el diputado José Luis Espert, acusado de recibir dinero de Federico «Fred» Machado, empresario extraditado a Estados Unidos por una causa narco, se tomó licencia alegando “motivos personales”, sino que la Cámara baja sancionó, por 140 votos a favor, 80 negativos y 17 abstenciones, la ley que limita el uso de los Decretos de Necesidad y Urgencia (DNU) por parte del Presidente. El gobierno anunció un clásico ya de esta gestión: el veto.

Por ahora, el proyecto avanza hacia el Senado.

Foto: Juan Valeiro para lavaca.org

El poco pan

La calle preveía este golpe, y por eso durante este miércoles se cantó:

“Si no hay aumento,

consiganló,

del 3%

que Karina se robó”.

Ese tema fue el hit del inicio de la jornada de este miércoles, aunque hilando fino carece de verdad absoluta, porque las jubilaciones de octubre sí registraron un aumento: el 1,88%, que llevó el haber mínimo a $326.298,38. Sumado al bono de 70 mil, la mínima trepó a $396 mil. “Es un valor irrisorio. Seguimos sumergidos en una vida que no es justa y el gobierno no afloja un mango, es tremendo cómo vivimos”, cuenta Mario, que no hay miércoles donde no diga presente. “Nos hipotecan el presente y el futuro también, cerrando acuerdos con el FMI que nos impone cómo vivir, y no es más que pan para hoy y hambre para mañana, aunque el pan para hoy te lo debo”.

Victoria tiene 64 años y es del barrio porteño de Villa Urquiza. Cuenta que desde hace 10 meses no puede pagar las expensas. Y que por eso el consorcio le inició un juicio. Cuenta que otra vecina, de 80, está en la misma. Cuenta que es insulina dependiente pero que ya no la compra porque no tiene con qué. Cuenta que su edificio es 100% eléctrico y que de luz le vienen alrededor de 140 mil pesos, más de un tercio de su jubilación. Cuenta que está comiendo una vez por día y que su “dieta” es “mate, mate y mate”. Vuelve a sonreír cuando cuenta que tiene 3 hijos y 4 nietos y cuando dice que va a resistir: “Hasta cuando pueda”.

A María Rosa la salvó la gente de que la policía la pasara por arriba. Foto: Juan Valeiro para lavaca.org

El mucho circo

Desde temprano hubo señales de que la represión policial estaba al caer. A diferencia de los miércoles anteriores, la Policía no cortó la avenida Rivadavia a la altura de Callao. Tampoco cortó el tránsito, lo que permitió que los jubilados y las jubiladas cortaran la calle para hacer semaforazos. Después de media hora, cuando la policía empezó a desviar el tránsito y la calle quedó desolada, comenzó la marcha, pero en vez de rodear la Plaza de los Dos Congresos como es habitual, caminó por Callao en dirección a Corrientes, hasta metros de la calle Sarmiento, donde se erigió un cordón policial y empezó a avanzar contra las y los manifestantes.

Desde atrás, irrumpieron con violencia dos cuerpos en moto: el GAM (Grupo de Acción Motorizada) y el USyD (Unidad de Saturación y Detención), pegando con bastones e insultando a quienes estaban en la calle. “Vinieron a pegarme directamente, mi pareja me quiso ayudar y lo detuvieron a él, que no estaba haciendo nada”, cuenta Lucas, el compañero de Cristian Zacarías, uno de los detenidos.

Foto: Juan Valeiro para lavaca.org

Cercaron el lugar una centena de efectivos de la policía porteña, que no permitieron a la prensa acercarse ni estar en la vereda registrando la escena.

“¿Alguien me puede decir si la detención fue convalidada”, pregunta Lucas al pelotón policial.

Silencio.

“¿Me pueden decir sí o no?”.

Silencio.

Un comerciante mira y vocifera: “¿Sabés lo que hicieron a la vuelta? Subieron a la vereda con las motos”.

Otro se acerca y pregunta: “¿A quién tienen detenido acá, al Chapo Guzmán?”

“No”, le responde seco un periodista: “A un pibe y a un jubilado”.

La Comisión Provincial por la Memoria confirmó las cuatro detenciones (fue aprehendida una quinta persona y derivada al SAME para su atención) y cuatro personas heridas. El despliegue incluyó la presencia también de Policía Federal, Prefectura y Gendarmería detrás del Congreso mientras el despliegue represivo fue «comandado por agentes de infantería de la Policía de la Ciudad». El organismo observó que después de semanas donde el operativo disponía el vallado completo, en los últimos miércoles el dispositivo dejó abierta una vía de circulación que es la que eligen las fuerzas para avanzar contra los manifestantes.

Foto: Juan Valeiro para lavaca.org

También se hizo presente Fabián Grillo, papá de Pablo, que sufrió esa represión el 12 de marzo, en esta misma plaza, y continúa su rehabilitación en el Hospital Rocca. “Su evolución es positiva”, comunicó la familia. El fotorreportero está empezando a comer papilla con ayuda, continúa con sonda como alimento principal, se sienta y se levanta con asistencia y le están administrando medicación para que esté más reactivo. “Seguimos para adelante, lento, pero a paso firme”, dicen familiares y amigos. El martes, la jueza María Servini procesó al gendarme Héctor Guerrero por el disparo. El domingo se cumplirán siete meses y lo recordarán con un festival.

Pablo Caballero mira toda esta disposición surrealista desde un costado. Tiene 76 años y cuatro carteles pegados sobre un cuadrado de cartón tan grande que va desde el piso del Congreso hasta su cintura:

- “Roba, endeuda, estafa, paga y cobra coimas. CoiMEA y nos dice MEAdos. Miente, se contradice, vocifera, insulta, violenta, empobrece, fuga, concentra. ¿Para qué lo queremos? No queremos, ¡basta! Votemos otra cosa”.

- “El 3% de la coimeada más el 7% del chorro generan 450% de sobreprecios de medicamentos”.

- El tercer cartel enumera todo lo que “mata” la desfinanciación: ARSAT, INAI, CAREM, CONICET, ENERC, Gaumont, INCAA, Banco Nación, Aerolíneas, Hidrovía, agua, gas, litio, tierras raras, petróleo, educación. Una enumeración del saqueo.

El cuarto cartel lo explica Pablo: “Cobro la jubilación mínima, que equivale al 4% de lo que cobran los que deciden lo que tenemos que cobrar, que son 10 millones de pesos. No tiene sentido. Por eso, hay que ir a votar en octubre”.

Pablo mira al cielo, como una imploración: «¡Y que se vayan!».

Foto: Juan Valeiro para lavaca.org

Foto: Juan Valeiro para lavaca.org

Foto: Juan Valeiro para lavaca.org

Artes

Un festival para celebrar el freno al vaciamiento del teatro

La revista Llegás lanza la 8ª edición de su tradicional encuentro artístico, que incluye 35 obras a mitad de precio y algunas gratuitas. Del 31 de agosto al 12 de septiembre habrá espectáculos de teatro, danza, circo, música y magia en 15 salas de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires. El festival llega con una victoria bajo el brazo: este jueves el Senado rechazó el decreto 345/25 que pretendía desguazar el Instituto Nacional del Teatro.

Por María del Carmen Varela.

«La lucha continúa», vitorearon este jueves desde la escena teatral, una vez derogado el decreto 345/25 impulsado por el gobierno nacional para vaciar el Instituto Nacional del Teatro (INT).

En ese plan colectivo de continuar la resistencia, la revista Llegás, que ya lleva más de dos décadas visibilizando e impulsando la escena local, organiza la 8ª edición de su Festival de teatro, que en esta ocasión tendrá 35 obras a mitad de precio y algunas gratuitas, en 15 salas de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires. Del 31 de agosto al 12 de septiembre, más de 250 artistas escénicos se encontrarán con el público para compartir espectáculos de teatro, danza, circo, música y magia.

El encuentro de apertura se llevará a cabo en Factoría Club Social el domingo 31 de agosto a las 18. Una hora antes arrancarán las primeras dos obras que inauguran el festival: Evitácora, con dramaturgia de Ana Alvarado, la interpretación de Carolina Tejeda y Leonardo Volpedo y la dirección de Caro Ruy y Javier Swedsky, así como Las Cautivas, en el Teatro Metropolitan, de Mariano Tenconi Blanco, con Lorena Vega y Laura Paredes. La fiesta de cierre será en el Circuito Cultural JJ el viernes 12 de septiembre a las 20. En esta oportunidad se convocó a elencos y salas de teatro independiente, oficial y comercial.

Esta comunión artística impulsada por Llegás se da en un contexto de preocupación por el avance del gobierno nacional contra todo el ámbito de la cultura. La derogación del decreto 345/25 es un bálsamo para la escena teatral, porque sin el funcionamiento natural del INT corren serio riesgo la permanencia de muchas salas de teatro independiente en todo el país. Luego de su tratamiento en Diputados, el Senado rechazó el decreto por amplia mayoría: 57 rechazos, 13 votos afirmativos y una abstención.

“Realizar un festival es continuar con el aporte a la producción de eventos culturales desde diversos puntos de vista, ya que todos los hacedores de Llegás pertenecemos a diferentes disciplinas artísticas. A lo largo de nuestros 21 años mantenemos la gratuidad de nuestro medio de comunicación, una señal de identidad del festival que mantiene el espíritu de nuestra revista y fomenta el intercambio con las compañías teatrales”, cuenta Ricardo Tamburrano, director de la revista y quien junto a la bailarina y coreógrafa Melina Seldes organizan Llegás.

Más información y compra de entradas: www.festival-llegas.com.ar

NotaHace 3 semanas

NotaHace 3 semanasComienza un juicio histórico por fumigaciones con agrotóxicos en Pergamino

NotaHace 3 semanas

NotaHace 3 semanasAdiós, Capitán Beto

PortadaHace 3 semanas

PortadaHace 3 semanasOtra marcha de miércoles: video homenaje a la lucha de jubiladas y jubilados

ActualidadHace 2 semanas

ActualidadHace 2 semanasReforma laboral: “Lo que se pierde peleando se termina ganando”

ActualidadHace 6 días

ActualidadHace 6 díasPablo Grillo con lavaca: “Quiero ver a Bullrich presa”