Nota

Stories from Argentina’s worker-run factories

Preface, Avi Lewis and Naomi Klein

On March 19, 2003, we were on the roof of the Zanon ceramic tile factory, filming an interview with Cepillo. He was showing us how the workers fended off eviction by armed police, defending their democratic workplace with slingshots and the little ceramic balls normally used to pound the Patagonian clay into raw material for tiles. His aim was impressive. It was the day the bombs started falling on Baghdad.

As journalists, we had to ask ourselves what we were doing there. What possible relevance could there be in this one factory at the southernmost tip of our continent, with its band of radical workers and its David and Goliath narrative, when bunker-busting apocalypse was descending on Iraq?

But we, like so many others, had been drawn to Argentina to witness firsthand an explosion of activism in the wake of its 2001 crisis – a host of dynamic new social movements that were not only advancing a bitter critique of the economic model that had destroyed their country, but were busily building local alternatives in the rubble.

There were many popular responses to the crisis, from neighbourhood assemblies and barter clubs to resurgent leftwing parties and mass movements of the unemployed, but we spent most of our year in Argentina with workers in «recovered companies.» Almost entirely under the media radar, workers in Argentina have been responding to rampant unemployment and capital flight by taking over traditional businesses that have gone bankrupt and are reopening them under democratic, worker management. It’s an old idea reclaimed and retrofitted for a brutal new time. The principles are so simple, so elementally fair, that they seem more self-evident than radical when articulated by one of the workers in this book: «We formed the cooperative with the criteria of equal wages, making basic decisions by assembly; we are against the separation of manual and intellectual work, we want a rotation of positions and, above all, the ability to recall our elected leaders.»

The movement of recovered companies is not epic in scale – some 170 companies, around 10,000 workers in Argentina. But six years on, and unlike some of the country’s other new movements, it has survived and continues to build quiet strength in the midst of the country’s deeply unequal «recovery». Its tenacity is a function of its pragmatism: this is a movement that is based on action, not talk. And its defining action, re-awakening the means of production under worker control, while loaded with potent symbolism, is anything but symbolic. It is feeding families, rebuilding shattered pride, and opening a window of powerful possibility.

Like a number of other emerging social movements around the world, the workers in the recovered companies are re-writing the traditional script for how change is supposed to happen. Rather than following anyone’s 10-point plan for revolution, the workers are darting ahead of the theory – at least, straight to the part where they get their jobs back. In Argentina, the theorists are chasing after the factory workers, trying to analyze what is already in noisy production.

These struggles have had a tremendous impact on the imaginations of activists around the world – at this point there are many more starry-eyed grad papers on the phenomenon than there are recovered companies. But there is also a renewed interest in democratic workplaces from Durban to Melbourne to New Orleans.

That said, the movement in Argentina is as much as product of the globalization of alternatives as it is one of its most contagious stories. Argentine workers borrowed the slogan, «Occupy, Resist, Produce» from Latin America’s largest social movement, Brazil’s Movimiento Sin Terra, in which more than a million people have reclaimed unused land and put it back into community production. One worker told us that what the movement in Argentina is doing is «MST for the cities». In South Africa, we saw a protester’s t-shirt with an even more succinct summary of this new impatience: Stop Asking, Start Taking.

But as much as these similar sentiments are blossoming in different parts of the world for the same reasons, there is an urgent need to share these stories and tools of resistance even more widely. For that reason, this translation that you are holding is of tremendous importance: it’s the first comprehensive portrait of Argentina’s famous movement of recovered companies in English.

The book’s author is the Lavaca collective, itself a worker cooperative like the struggles documented here. While we were in Argentina filming our documentary, The Take, we ran into Lavaca members wherever the workers’ struggles led – the courts, the legislature, the streets, the factory floor. They do some of the most sophisticated engaged journalism in the world today.

And this book is classic Lavaca. That means it starts with a montage – a theoretical framework that is unabashedly poetic. Then it cuts to a fight scene of the hard facts: the names, the numbers, and the M.O. behind the armed robbery that was Argentina’s crisis. With the scene set, the book then zooms in to the stories of individual struggles, told almost entirely through the testimony of the workers themselves.

This approach is deeply respectful of the voices of the protagonists, while still leaving plenty of room for the authors’ observations, at once playful and scathing. In this interplay between the cooperatives that inhabit the book and the one that produced it, there are a number of themes that bear mention.

First of all, there is the question of ideology. This movement is frustrating to some on the left who feel it is not clearly anti-capitalist, those who chafe at how comfortably it exists within the market economy and see worker management as merely a new form of auto-exploitation. Others see the project of cooperativism, the legal form chosen by the vast majority of the recovered companies, as a capitulation in itself – insisting that only full nationalization by the state can bring worker democracy into a broader socialist project.

In the words of the workers, and in between the lines, you get a sense of these tensions and the complex relationship between various struggles and parties of the left in Argentina. Workers in the movement are generally suspicious of being coopted to anyone’s political agenda, but at the same time cannot afford to turn down any support. But more interesting by far is to see how workers in this movement are politicized by the struggle, which begins with the most basic imperative: workers want to work, to feed their families. You can see in this book how some of the most powerful new working class leaders in Argentina today discovered solidarity on a path that started from that essentially apolitical point.

But whether you think the movement’s lack of a leading ideology is a tragic weakness or a refreshing strength, this book makes clear precisely how the recovered companies challenge capitalism’s most cherished ideal: the sanctity of private property.

The legal and political case for worker control in Argentina does not only rest on the unpaid wages, evaporated benefits and emptied-out pension funds. The workers make a sophisticated case for their moral right to property – in this case, the machines and physical premises – based not just on what they’re owed personally, but what society is owed. The recovered companies propose themselves as an explicit remedy to all the corporate welfare, corruption, and other forms of public subsidy the owners enjoyed in the process of bankrupting their firms and moving their wealth to safety, abandoning whole communities to the twilight of economic exclusion.

This argument is, of course, available for immediate use in the United States.

But this story goes much deeper than corporate welfare. And that’s where the Argentine experience will really resonate with Americans. It’s become axiomatic on the left to say that Argentina’s crash was a direct result of the IMF orthodoxy imposed on the country with such enthusiasm in the neoliberal 1990s. What this book makes clear is that in Argentina, just as in the U.S. occupation of Iraq, those bromides about private sector efficiency were nothing more than a cover story for an explosion of frontier-style plunder – looting on a massive scale by a small group of elites. Privatization, deregulation, labor flexibility: these were the tools to facilitate a massive transfer of public wealth to private hands, not to mention private debts to the public purse. Like Enron traders, the businessmen who haunt the pages of this book learned the first lesson of capitalism and stopped there: greed is good, and more greed is better. As one worker says in the book, «There are guys that wake up in the morning thinking about how to screw people, and others who think, how do we rebuild this Argentina that they have torn apart?

And in the answer to that question, you can read a powerful story of transformation. This book takes as a key premise that capitalism produces and distributes not just goods and services, but identities. When the capital and its carpet baggers had flown, what was left was not only companies that had been emptied, but a whole hollowed-out country filled with people whose identities – as workers – had been stripped away too.

As one of the organizers in the movement wrote to us, «It is a huge amount of work to recover a company. But the real work is to recover a worker – and that is the task that we have just begun.»

On April 17, 2003, we were on Avenida Jujuy in Buenos Aires – standing with the Brukman workers and a huge crowd of their supporters in front of a fence, behind which was a small army of police guarding the Brukman factory. After a brutal eviction, the workers were determined to get back to work at their sewing machines.

In Washington DC that day, USAID announced that it had chosen Bechtel corporation as the prime contractor for the reconstruction of Iraq’s architecture. The heist was about to begin in earnest, both in the US and in Iraq. Deliberately-induced crisis was providing the cover for the transfer of billions of tax dollars to a handful of politically-connected corporations.

In Argentina, they’d already seen this movie – the wholesale plunder of public wealth, the explosion of unemployment, the shredding of the social fabric, the staggering human consequences. And 52 seamstresses were in the street, backed by thousands of others, trying to take back what was already theirs. It was definitely the place to be.

Avi Lewis and Naomi Klein

Nota

De la idea al audio: taller de creación de podcast

Todos los jueves de agosto, presencial o virtual. Más info e inscripción en [email protected]

Taller: ¡Autogestioná tu Podcast!

De la idea al audio: taller de creación de podcast

Aprendé a crear y producir tu podcast desde cero, con herramientas concretas para llevar adelante tu proyecto de manera independiente.

¿Cómo hacer sonar una idea? Desde el concepto al formato, desde la idea al sonido. Vamos a recorrer todo el proceso: planificación, producción, grabación, edición, distribución y promoción.

Vas a poder evaluar el potencial de tu proyecto, desarrollar tu historia o propuesta, pensar el orden narrativo, trabajar la realización sonora y la gestión de contenidos en plataformas. Te compartiremos recursos y claves para que puedas diseñar tu propio podcast.

¿A quién está dirigido?

A personas que comunican, enseñan o impulsan proyectos desde el formato podcast. Tanto para quienes quieren empezar como para quienes buscan profesionalizar su práctica.

Contenidos:

- El lenguaje sonoro, sus recursos narrativos y el universo del podcast. De la idea a la forma: cómo pensar contenido y formato en conjunto. Etapas y roles en la producción.

- Producción periodística, guionado y realización sonora. Estrategias de publicación y difusión.

- Herramientas prácticas para la creación radiofónica y sonora.

Modalidad: presencial y online por Zoom

Duración: 4 encuentros de 3 horas cada uno

No se requiere experiencia previa.

Docente:

Mariano Randazzo, comunicador y realizador sonoro con más de 30 años de experiencia en radio. Trabaja en medios comunitarios, públicos y privados. Participó en más de 20 proyectos de podcast, ocupando distintos roles de producción. También es docente y capacitador.

Nota

Darío y Maxi: el presente del pasado (video)

Hoy se cumplen 23 años de los asesinatos de Darío Santillán y Maximiliano Kosteki que estaban movilizándose en Puente Pueyrredón, en el municipio bonaerense de Avellaneda. No eran terroristas, sino militantes sociales y barriales que reclamaban una mejor calidad de vida para los barrios arrasados por la decadencia neoliberal que estalló en 2001 en Argentina.

Aquel gobierno, con Eduardo Duhalde en la presidencia y Felipe Solá en la gobernación de la provincia de Buenos Aires, operó a través de los medios planteando que esas muertes habían sido consecuencia de un enfrentamiento entre grupos de manifestantes (en aquel momento «piqueteros»), como suele intentar hacerlo hoy el gobierno en casos de represión de sectores sociales agredidos por las medidas económicas. Con el diario Clarín a la cabeza, los medios mintieron y distorsionaron la información. Tenía las imágenes de lo ocurrido, obtenidas por sus propios fotógrafos, pero el título de Clarín fue: “La crisis causó 2 nuevas muertes”, como si los crímenes hubieran sido responsabilidad de una entidad etérea e inasible: la crisis.

Darío Santillán.

Maximiliano Kosteki

Del mismo modo suelen mentir los medios hoy.

El trabajo de los fotorreporteros fue crucial en 2002 para desenmascarar esa mentira, como también ocurre por nuestros días. Por aquel crimen fueron condenados el comisario de la bonaerense Alfredo Franchiotti y el cabo Alejandro Acosta, quien hoy goza de libertad condicional.

Siguen faltando los responsables políticos.

Toda semejanza con personajes y situaciones actuales queda a cargo del público.

Compartimos el documental La crisis causó 2 nuevas muertes, de Patricio Escobar y Damián Finvarb, de Artó Cine, que puede verse como una película de suspenso (que lo es) y resulta el mejor trabajo periodístico sobre el caso, tanto por su calidad como por el cúmulo de historias y situaciones que desnudan las metodologías represivas y mediáticas frente a los reclamos sociales.

Nota

83 días después, Pablo Grillo salió de terapia intensiva

83 días.

Pasaron 83 días desde que a Pablo Grillo le dispararon a matar un cartucho de gas lacrimógeno en la cabeza que lo dejó peleando por su vida.

83 días desde que el fotógrafo de 35 años se tomó el ferrocarril Roca, de su Remedios de Escalada a Constitución, para cubrir la marcha de jubilados del 12 de marzo.

83 días desde que entró a la guardia del Hospital Ramos Mejía, con un pronóstico durísimo: muerte cerebral y de zafar la primera operación de urgencia la noche del disparo, un desenlace en estado vegetativo.

83 días y seis intervenciones quirúrgicas.

83 días de fuerza, de lucha, de garra y de muchísimo amor, en su barrio y en todo el mundo.

83 días hasta hoy.

Son las 10 y 10 de la mañana, 83 días después, y ahí está Pablito, vivito y sonriendo, arriba de una camilla, vivito y peleándola, saliendo de terapia intensiva del Hospital Ramos Mejía para iniciar su recuperación en el Hospital de Rehabilitación Manuel Rocca, en el barrio porteño de Monte Castro.

Ahí está Pablo, con un gorro de lana de Independiente, escuchando como su gente lo vitorea y le canta: “Que vuelva Pablo al barrio, que vuelva Pablo al barrio, para seguir luchando, para seguir luchando”.

Su papá, Fabián, le acaricia la mejilla izquierda. Lo mima. Pablo sonríe, de punta a punta, muestra todos los dientes antes de que lo suban a la ambulancia. Cuando cierran la puerta de atrás su gente, emocionada, le sigue cantando, saltan, golpean la puerta para que sepa que no está solo (ya lo sabe) y que no lo estará (también lo sabe).

Su familia y sus amigos rebalsan de emoción. Se abrazan, lloran, cantan. Emi, su hermano, respira, con los ojos empapados. Dice: “Por fin llegó el día, ya está”, aunque sepa que falta un largo camino, sabe que lo peor ya pasó, y que lo peor no sucedió pese a haber estado tan (tan) cerca.

El subdirector del Ramos Mejía Juan Pablo Rossini confirma lo que ya sabíamos quienes estuvimos aquella noche del 12 de marzo en la puerta del hospital: “La gravedad fue mucho más allá de lo que decían los medios. Pablo estuvo cerca de la muerte”. Su viejo ya lloró demasiado estos casi tres meses y ahora le deja espacio a la tranquilidad. Y a la alegría: “Es increíble. Es un renacer, parimos de nuevo”.

La China, una amiga del barrio y de toda la vida, recoge el pasacalle que estuvo durante más de dos meses colgado en las rejas del Ramos Mejía exigiendo «Justicia por Pablo Grillo». Cuenta, con una tenacidad que le desborda: «Me lo llevo para colgarlo en el Rocca. No vamos a dejar de pedir justicia».

La ambulancia arranca y Pablo allá va, para continuar su rehabilitación después del cartucho de gas lanzado por la Gendarmería.

Pablo está vivo y hoy salió de terapia intensiva, 83 días después.

Esta es parte de la vida que no pudieron matar:

Revista MuHace 4 semanas

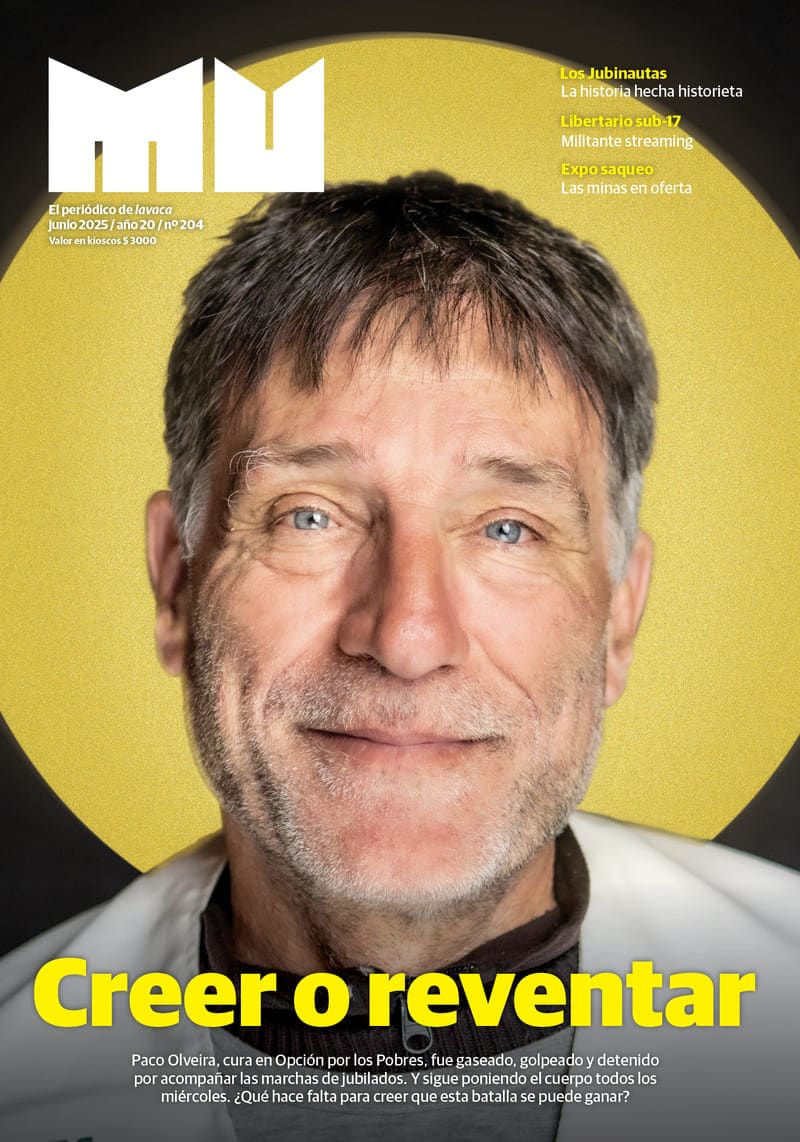

Revista MuHace 4 semanasMu 204: Creer o reventar

AmbienteHace 4 semanas

AmbienteHace 4 semanasContaminación: récord histórico de agrotóxicos en el Río Paraná

ArtesHace 2 semanas

ArtesHace 2 semanasVieron eso!?: magia en podcast, en vivo, y la insolente frivolidad

ActualidadHace 4 semanas

ActualidadHace 4 semanasLos vecinos de Cristina

#NiUnaMásHace 2 semanas

#NiUnaMásHace 2 semanasActo trans por más democracia